There were shots of actors and singers and comedians: people like Sally Field, Henry Winkler, William Shatner, Mickey Rooney, Frankie Avalon and Billy Crystal. And there were athletes like Chicago Cubs legend Ernie Banks and welterweight and middleweight champ Carmen Basilio.

But those gathered paid no attention to the stars.

All their attention was focused on the headliner at the front of the room. To them, he had the celebrity status, the athletic triumph that matched anything you found on the wall.

Larry Smith sat there in his blue polo shirt and dark glasses as he worked his way through one small paper plate filled with squares of pizza and then another.

It was the eve of his 87th birthday – he was born on the Fourth of July in 1938 – and many of his friends, some of whom have known and helped him for over half a century, had gathered to share stories and tell him what he meant to them.

Teresa Winner of the Versiti Blood Donation Center spoke for everyone when she said: “Larry, you are a treasure!”

When he was six months old, Smith was left on the doorstep of a Marion County Children’s Home by his mother. He was found the next morning by an eight-year-old girl who took him inside, where he was given his name.

Steve Wirick – a retired engineer from Vandalia who is Larry’s friend, his power of attorney and an accomplished fellow runner – set up the party and then provided some backstory for the crowd:

“Larry had a tough start in life. His mother was a prostitute who had four children by four different men. Maybe when she realized he was blind, she abandoned him.”

When we first met over a couple of decades ago, Larry shared much of his story with me.

For years at that orphanage, he said he and the other children were beaten, verbally abused and given minimal food.

With no family support to draw on and almost no love given to him in his immediate surroundings, he said he was “on the verge of a mental breakdown” when he was just six.

He said an attendant, angry that he’d used a newly-polished railing to support himself going down a stairway, cuffed him so hard on the side of the head that his eardrum burst.

Other people in positions of authority at the orphanage told him he was worthless and, because of his blindness, he would amount to nothing in his life.

It wasn’t until he was 13 that authorities – after finding two bloodied boys who’d run away from the facility – finally discovered the inhumane conditions at the orphanage. The director was ousted and a new, more nurturing staff was brought in and life finally changed for Larry.

“It was horrible so long, but finally I started living,” he told me. “And that’s when I vowed I was going to make something of myself. I was going to be whatever I wanted.”

And that’s just what he did.

After going through the Ohio School for the Blind, he got the support of Goodwill Industries, which found him a job in the darkroom at Grandview Hospital in Dayton.

From then on, he proved time after time that those abusers and belittlers at the orphanage were the ones who couldn’t see.

At Thursday’s party, one person after another stepped forward to tell how Larry Smith had opened their eyes to the possibilities of life.

“There’s nothing that Larry’s afraid of trying,” said Ruth Weidner of Beavercreek who attended Mt. Zion Church with him.

She recounted how he joined the church choir and knew all the songs off the top of his head. She told how he plays the harmonica, loves to eat, has driven the family’s pontoon boat at Indian Lake and even rode a jet ski.

Harry Bradbury remembered Larry bowling in a league.

Tim Edgar, who’s also blind, and worked with Larry at Grandview, talked about their friendship; their love of music and how they used to cook dinner for each other every Monday evening.

But the two areas where Smith really has made a name for himself are as a blood donor and a distance runner.

Both pursuits have gotten him Hall of Fame recognition:

- The Fresenius Kabi Blood Donation Hall of Fame made him part of its select, 12-member induction class in 2015 for his extraordinary efforts. Today, a decade after that honor, he’s upped his total to 451 lifetime blood donations. Most of them lately have been platelets and plasma.

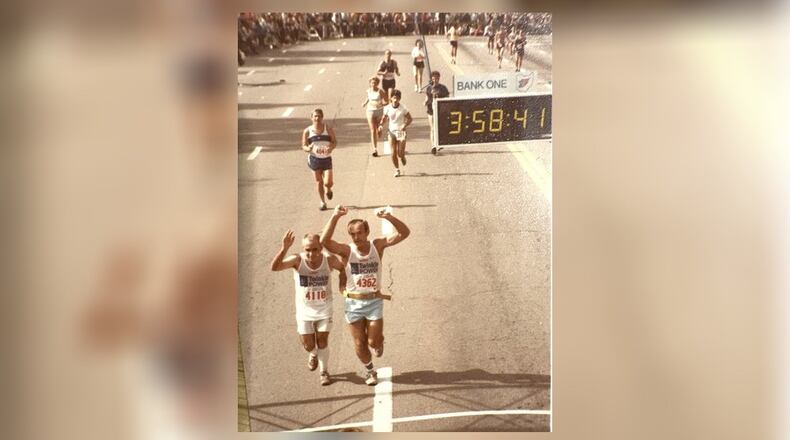

- In 1989, the Dayton Distance Runners Hall of Fame enshrined him and Bradbury, his longtime running partner.

With Bradbury wearing a scuba belt with a suitcase handle affixed to the back of it – and Larry hanging onto him with one hand – they have competed in three marathons, 50 half marathons and numerous other events.

Although Bradbury suffered severe cramps in two of those marathons and was forced to the sidelines – at the Boston Marathon, dizzy and dehydrated, he was taken away in an ambulance – Larry just found a new partner and finished each 26.2 mile race.

Over the years, Larry has run more than 75,000 miles – the equivalent of over three trips around the globe. With each 25,000-mile accomplishment, Bradbury awarded him a globe.

Larry has partnered with other sighted partners over the years and once, when he teamed with Sunji Hashimoto at the Dayton River Classic Corridor, he clocked a 6:13 pace in the half marathon, something Wirick, a veteran of over 150 marathons and ultra-marathons, said he never could do.

Although he spent all those decades running with Bradbury, as well as regularly going to lunch and dinner with him, as well as taking part in myriad social opportunities with him, Larry once admitted he didn’t really know what Bradbury looked like.

“I’ve tried to make a mental picture,” he said. “From running with him, I know he’s not tall and not fat. I heard he wears glasses, but I don’t know the color of his hair, his eyes, nothing like that. But looks can be deceiving.

“So, what Harry looks like doesn’t really matter. I only see personality; I only see heart. That’s why I think Harry must be pretty handsome.”

Thanks to Larry, the 94-year-old Bradbury now has similar vision himself:

“When I look at Larry, all I see any more is my old friend, someone who has inspired me all these years.

“Larry has never let his blindness be the overriding part of his life, so I don’t really see a guy with a handicap.

“I see beyond that.”

Runner’s high

When he came to Dayton, Larry lived, among other places, in a room in a boarding house on Grand Avenue and at the YMCA, where Lou Cox, the long-time fitness director, got him started jumping rope.

When the facility added an overhead running track in 1970, Bradbury said, a YMCA member coaxed Larry into joining him up there and they interlocked arms and started making circuits:

“They only went two or three laps and Larry said, ‘This is not for me!’

“And the member said, ‘Oh yes it is! And if you don’t come here, I’m going to go get you.’”

As it turned out, the member was right, and Larry embraced running.

“It released endorphins to the brain and became like an addiction to me,” he said. “It gave me a runner’s high and became a feeling I loved.

“It made me feel good about myself.”

As Larry trained on the track, he drew people to him, including the young LaRen Rodgers, who was preparing for football at nearby Patterson Co-Op High.

LaRen came to Thursday evening’s gathering and told how he used to train with Larry and how his whole family got to know him. Soon Larry was visiting them at their home and he went to church with LaRen down in Middletown.

Larry Hudson was at the birthday party, as well, and remembered coming to the YMCA 62 years ago when he was 11 years old:

“I was taking swimming lessons at the Y and our whole family came for the Family Swim one Saturday night. When we were getting in the water, my mother noticed Larry on the edge of the pool, kind of hanging back.

“He didn’t know what to expect in a room full of strangers. My mom said he looked kind of lonely over there and sent me over.”

After doing some laps with Larry, Hudson hurried back to his family and excitedly told his mother: “Mom, his name is Larry, too! . . . And he’s blind!’”

It turned out their birthdays were just two days apart. Larry Hudson was born on July 2.

That first night, the Hudson family gave Larry a ride back to the Dayton boarding house where he was living and asked if he’d come visit them at their home.

A bond formed, and Larry began joining the Hudsons for dinner every Christmas Day, Labor Day and the Fourth of July for a dual birthday celebration.

Back in those early days Hudson said his family had access to the Frigidaire Recreation Park in Harrison Township: “All summer they had (outdoor) movies and you’d put blankets down and sit and watch. My job was to sit next to Larry and tell him what was going on. I narrated all kinds of Gidget goes here and Gidget goes there movies that summer.

“We’ve been great friends all these years.”

While Larry was experiencing some of the best in humanity, the worst also surfaced again.

Some bullies used to try to trip him and would jostle him and once robbers entered into his boarding house room with guns and tried to rob him.

Incidents like that, coupled with the early abuse he suffered, took a toll on him.

A happy ending

“I used to be very bitter,” Larry told the crowd Thursday evening. “I’d tell people I hate so and so for what he did to me. ‘As far as I care, those people can rot and burn in hell.’

“But when I was at church, George Reynolds, who was a judge here, saw how I was. He saw my bitter nature and said, ‘Larry, you’ve got to let all that go. You’ve been forgiven and you have to forgive others, too.’

“But I said, ‘No, I can’t do it. I hate those robbers and if I had a hammer I’d smash them on the head.’

“So he just told me he’d pray for me.

“But that weighed on my mind and I had some nights where I couldn’t sleep, too well. It was almost like someone was talking to me and telling me:

“’You must forgive!’”

“’You must forgive!’”

“And I finally gave into it and when everything lifted – I had carried that burden for years and years - I was free.

“The next time George saw me he could tell by the look on my face. He said. ‘You forgave, didn’t you?’ I said I had, and I felt fine. I was free.”

In recent times, he’s focused on the good in people and has given back any way he could.

That’s evident in his twice monthly trips to the blood bank and his focus on children in need.

As Larry’s power of attorney, Wirick sees Larry’s goodness in ways others have not.

He writes Larry’s checks for him and said: “Larry’s very generous especially when it comes to children.”

Even though Larry’s on a fixed income and Wirick keeps warning him to hold back, Larry is insistent and gives to places like Dayton Children’s, St. Jude Children’s Hospital and an Indian school.

“He remembers how it was for him as a kid,” Wirick said.

Today Smith lives at the Austin Trace Health and Rehabilitation center in Washington Township. He still does exercises in his room and has impressed Kaia James, the case manager there:

“I call him Mr. Larry, and he is the G.O.A.T. He is the greatest. I’m there to help him, but he’s given me lessons about persistence and sticking up for yourself.”

Both Bradbury and Wirick said they have been glad to help Larry because first and foremost he’s worked to help himself.

Even so, Weidner got emotional when she thought about what Bradbury and Wirick have done for him:

“I can’t stand up here and not say enough about Harry and Steve,” she said as her voice began to break. “They have been an absolute gift from God.”

Wirick, though, was quick to turn the focus back on Larry:

“His story is going to have a happy ending.”

It already has, and Thursday’s outpouring of love was proof.

“This was a great day,” Larry said. “All my friends were here.

“I’ll tell you, it’s been great seeing them all today.”

About the Author